Review #5 of 2024: Del sentimento trágico de La Vida

El primero de mis libros de terminar antes de morir: coincidentemente íntimamente relacionado con este tema

Reseña Corta en Español

Descubrí Unamuno por tres caminos diferentes. Uno: sus palabras son citados en un libro sobre Ortega y Gasset (Ortega y Gasset para Profanos) porque su pensamiento es, de una forma, algo parecido a lo de Ortega y Gasset. Yo leí esto por mejorar mi conocimiento de filósofos españoles. También, Unamuno (y por extension su filosofía) es el protagonista de una película que se llama Mientras dure la guerra, sobre los primeros días de la guerra civil en España. Unamuno tiene un discurso muy importante (pero probablemente falsificado) en la escena final que me gusta mucho. El camino final fue un comparison en YouTube entre Kierkegaard y Unamuno. Kierkegaard es alguno de los más importantes pensadores en mi vida, pero el es hereje (soy Católica). Unamuno no tiene esta cualidad. Por estos tres razones, decidí añadir este libro a mi lista de diez libros, y recomendarlo a mi grupo de filosofía.

El tema principal de este novela es la urgencia de creer en algo más allá de nuestra vida aquí en la tierra. Lo que Unamuno quiere decir exactamente es un poco vago: la imagen de esta vida “más allá” no tiene forma concreta. Lo importante es que la vida continua de alguna forma porque Unamuno (y según él todos nosotros) tiene un gran miedo de dejar de existir. Pero no podemos tener seguridad en este continuación de vida, a pesar de las aseguraciones de la iglesia. Necesitamos, y francamente, debemos tomarlo en nuestras mentes como un salto de fe. Y sea este salto de fe que nos nutre y alimenta nuestra vida cotidiana. Y sea necesario: sin esperanza seamos lleno de depresión, sin duda seamos sin motivación. Parece muy similar a Kierkegaard.

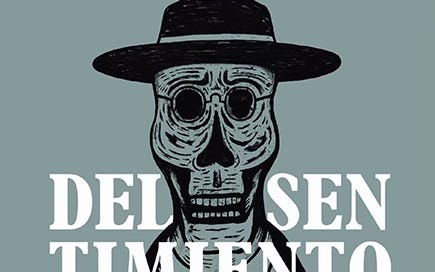

Hay otros temas interesantes dentro: una defensa de catolicismo como “medio de oro” entre protestantismo y la fe Christiana de oriente, un análisis personal de hombres desde su filosofía, y una exigencia a vivir nuestras vidas cómo seamos dignos de la vida eternal (con rectitud y moralidad). Mi edición también es llena de ilustraciones buenos (algunos son un poco pavorosos), y la recomendó.

Background

The first of my ten books done! I should finish another couple this year, which is a pace I’m quite happy with (and will let me write another list within a year or two). I plan on writing a review for each book and posting them on the main page as I read them.

I discovered Unamuno and this book through the Spanish Philosopher José Ortega y Gasset, a Spanish movie about the beginnings of the Spanish Civil War (Mientras dure la guerra) , and through his association with Kierkegaard. I converted to Catholicism Easter 2023, and Kierkegaard existentialist understanding of Christianity was one of the reasons for doing so. However, Kierkegaard was a protestant, and his understanding of the faith very individualistic. Unamuno was exactly who I was looking for, someone who wedded the existentialist understanding of Christianity with the communal emphasis of Catholicism. I managed to get my philosophy book club on board with this book as well, so Tommy, Simon, Amanda, Logan, Tessa, Dylan, and myself embarked on the journey of reading this book in June of 2024. I did so in Spanish, while the rest of the group did so in English.

The central premise, which also informs the title of this book, is that the main reason for tragedy in our lives is the fear that we are one day going to die. It is through having faith (not certainty) against this fear that we are able to find nourishment and hope. However, Unamuno is a philosopher more in the style of Nietzche than the analytics, and the essays that he collects in this book are all over the place, from the failures of scholasticism as an answer to the problems of the Church, the Aristotelean “golden mean” of Catholicism as compared to Protestantism or Eastern Christianity, to the relationship between the philosopher and his philosophy1 . I’ll also talk a little bit about the difficulty of reading philosophy in Spanish.

Central premise: the tragic sense of life

As I stated earlier, the central point of this collection of essays is to grapple with the “tragic sense of life” that some individuals (and also countries) seem to have. This tragic sense of life stems from the recognition that death is probable, but also that we really, really don’t want to die. This problem as a premise caused some level of disagreement within the philosophy book club. About half the people in the club just don’t experience this kind of death anxiety at all, which, as someone who does, was very strange. I can understanding wanting to leave specific life circumstances, but doesn’t everyone want to keep having a conscious experience of the world, no matter what? Where do my readers stand on this?

Unamuno’s solution is to trust in the existence of a god who would not allow us to experience suffering of this kind, and thus to have faith in some kind of after life or continuation of our conscious experience. Very importantly, this is an act of faith, not of knowledge. We must always have doubt, be unsure, about the real eternity of life, lest we grow complacent in the living of this life in the here and now. It is the struggle for hope and belief in eternal life that brings salvation, not the belief itself. The absurdity of this philosophy leads Unamuno to name Don Quijote as its champion, and the Spanish people as his flag bearers. For him, the hero who would tilt at windmills, and laugh in the face of sure defeat, is the model we should strive to emulate. This aspect of his argument wasn’t the clearest to me, but I think that is at least partially due to having not read Quijote.

Against reason

Unamuno also comes off as quite against the exclusive use of reason in religion, politics, and philosophy. Echoing Iain McGilchrist (or more accurately, McGilchrist echoing Unamuno), he decries the overemphasis on scholasticism in the Catholic church, and the overemphasis on logic in philosophy. Again this was a contentious point in our book club. Pretty much everyone agreed with the way McGilchrist framed this critique: that we have lost touch with our intuition, and that logic makes a very-poor foundation for any philosophical or moral system (although an excellent servant). Unamuno ends up throwing the baby out with the bathwater here, dismissing logic almost entirely. And with the examples he gives, it makes sense why. First he talks about the scholastics, church fathers from the Middle Ages who tried to use Aristotelean logic to prove the existence of God. Having read some of their arguments in church and during book club, these arguments are laughably circular and rest on the intuition that God already exists and is good. So why use logic at all, when intuition would suffice? He also discusses Kant, whose intuitions are the same as the Christians, but without a God, and thus lead him to the same moral framework. Again, no need for logic.

Unamuno also makes the point that reason, and logic are unchanging and eternal things, and thus are in a sense, dead. For someone who thinks that struggle, change, and life are the most sacred things in life, reason would obviously appear to be corrosive and poisonous. But I, like McGilchrist and the rest of our book club, don’t see how you can construct a philosophical system, a worldview, or a life without some amount of reason. It’s just important to keep reason as a servant to the master of intuition, rather than the other way round.

Philosophy in a second language

It’s honestly not as bad as it seems to try and read philosophy in Spanish. Due to the philosophical vocabulary of both languages sharing Latin and Greek roots, many words are actually quite similar. What is actually much more difficult is the references to other philosophers and their works that I’m not familiar with. This would be a difficulty in English as well, but the added difficulty of not knowing ~10% of the words on the page made figuring why Unamuno was bringing up that particular philosophical example that much harder. This has improved quite a bit since I started philosophy book club just because of the growing familiarity with philosophy as an academic discipline that this practice has engendered, but I also expect that it will continue to improve as I read more Spanish philosophy in general.

How I will be changing my life as a result of this book

The biggest thing that this book has assured me of is the ability to question and refine my own thoughts about the catholic faith, independent of what any church dogma says. I can still call myself a Catholic and believe in things like reincarnation and panpsychism, as Unamuno did, although this book was labeled as heretical by the Vatican. That does beg the question of what changes in belief would cause me to no longer identify as a catholic. To me, the heart of the catholic faith is the belief that the road to salvation lies in loving they neighbor as thyself, as Jesus did, and doing so in communion with christ and the rest of the church. It is all well and good to think about these metaphysical problems, but at the end of the day, the core of catholicism is coming together to celebrate mass every Sunday, and trying my utmost to be a loving person. When I no longer believe one of those two things, it’s time to hang up the cross.

This book also made me realize how much more I have to read to really understand what these philosophers are saying. Next up on the 10 books is DFW’s Infinite Jest!

If you liked this review, please subscribe to the newsletter! This year I will be aiming for a blog post a week, following a rotation of personal updates, book reviews, running writings, and crunchy updates, as well as Spanish and Italian learning updates as we get to them. If you’d like to chat about Unamuno or anything else, leave a comment below or shoot me an email at deusexvitablog@gmail.com.

Note: all links to books in this essay are affiliate links to amazon. The books are good. I’ve read them. If you’d rather support local businesses, I’m a big proponent of that.

Usually, in Unamuno’s opinion, the philosophy is a “cope” or “wish” about the way things should be rather a rational analysis of the world as they see it.