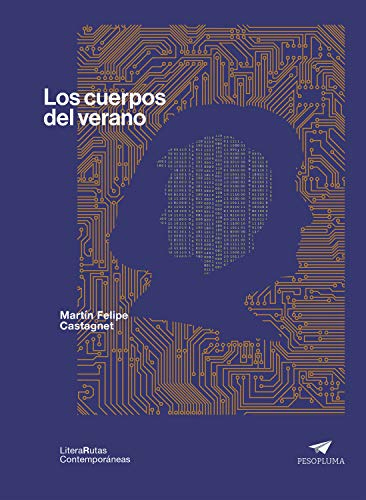

Review #10 of 2023: Los Cuerpos del Verano

A chilling science fiction novella in which death is abolished and society embraces transhumanism fully

Reseña Corta en Español: Imagina un mundo sin muerte. Pero en vez de vivir en tu cuerpo para siempre, necesitas cambiar cuerpos cada vez que mueres o haces demasiado daño a ti mismo. Y la calidad de tu cuerpo futuro depende de la cantidad de dinero que puedes gastar. Capitalismo por una eternidad! Esto es el mundo de la novelita del escritor argentino Matin Felipe Castagnet: Los cuerpos del verano. La trama de esta novela concentra en la vida de un tal Ramiro que reencarna en un cuerpo de una mujer gorda de edad bastante avanzada. El libro sigue Ramiro en este cuerpo (y otros también) durante él trata de encontrar la familia de su esposa muerte, tomar venganza contra un viejo amigo y acostumbrarse a este nuevo mundo. Algo corte, pero siempre llena de sorpresas y profundidades lo recomiendo Los cuerpos del verano a todos. La ciencia ficción es un espejo a nuestro mundo y nuestro futuro. La transhumanidad, extension de vida, alienación de su propio ya están aquí. Solamente, esas temas van más allá en el mundo de este libro. Lo me da mucho a pensar, y realmente es un de los libros de ciencia ficción más excelentes que lo he leído en español o mi lengua materna.

Los cuerpos del verano (The Bodies of Summer in English) is the first novela of Argentinian writer Martín Felipe Castagnet. I read it in Spanish and I recommend you do the same, as the prose is beautiful, and I’m not sure that the English translation does it justice. Even the title doesn’t sound quite as good in my native language as in Castillano. The book centers on Ramiro, a man who has just been revived into the body of a middle-aged woman from a hundred-year state of suspended animation on the internet. The short book’s plot deals with Ramiro adapting to this new body and trying to navigate the complex social situations of a future in which no one really dies. This novela has been compared in the past to an episode of Black Mirror, and I think that comparison is accurate. However, I found “Los Cuerpos del Verano” to be much deeper than your typical Black Mirror episode, and it gave me a lot of food for thought. I’ll elaborate on three mindworms I’ve had below: transhumanism, the value of death, and out-of-control nature of technological development.

The destruction of extreme Transhumanism

Nobody dies voluntarily in the future in “Los cuerpos del verano”. When you die, your consciousness is uploaded to the internet, to await uploading into a recycled body, which functions with the help of some embedded electronics. The amount of money you, or more likely your family, is willing to pay determines what quality of body you get. Poor? Your new body is fat, middle-aged and ugly. Rich? It’s fit and attractive. Super-poor? You just get your former rotting corpse, with no chance of further incarnation1. While death doesn’t seem to change this aspect of our capitalistic system, it does allow a never-before seen level of opportunity for transhumanists and gnostics: allowing us to become whatever race, gender, or body-type that you want. If you have the money that is.

I think Castagnet shows both that a). this is not actually good for society and b). this extreme mind-body dualism doesn’t actually work the way gnostics would like to believe.

“El otro día escuché que un hombre fue eutanizado para ocupar el cuerpo de su mujer, muerta por accidente cerebrovascular; luego, la mujer encarnó en el cuerpo de su esposo que esperaba vacío en un frigorífico del hospital”

The other day I heard that a man was euthanized in order to occupy the body of his wife, who had died due to a stroke; later, the wife was reincarnated in the body of her spouse that waited empty in a refrigerator in the hospital. (Translation mine).

There’s so much destruction entailed in this radical idea of transhumanism: that we can be whatever we want. Like it or not, we have roles to play in society and our families. Being whatever we want necessarily conflicts with that. We get to see this first hand when the main character’s grandson decides that he wants to be a woman, tearing his marriage apart. We also see this in the narration of our main character, and his profound sense of alienation, even among his own family. His familiar world of people who stay looking the same is gone, leaving him adrift in a sea where nothing is stable. Perhaps this is why Ramiro is so drawn to the panchama, Cuzco, who works in his household. At least his body is always the same.

But even this radical transhumanism doesn’t go as far as the true mind-body dualists would like to believe. Each body that Ramiro lives in alters the function of his mind in subtle ways. As a woman he likes putting on make-up. As a horse (yes a horse) he feels pleasure merely walking around. He also enjoys the very existence of just being embodied, rather than floating around on the net, which the pure idealists would find horrifying. The gnostic idea of the mind really being independent from the body is clearly false in this world.

Death grounds us

“The last enemy to be destroyed is death” (1 Corinthians 15:26)

This is a world in which death has vanished. The old cemeteries have been converted into slums. The funerals and wakes have stopped. Almost everyone is uploaded to the net after their death, to await reincarnation. This is the dream of another forward-thinking group, the Rationalists/Effective Altruists. I think this was most famously put in Nick Bostrom’s essay the myth of the Dragon Tyrant. I used to agree with the sentiment espoused by the rationalist. Why on Earth would we want everyone we know and love, including ourselves to die? Now I’m not sure. It doesn’t seem necessarily obvious to me, or atheists philosophers like Schopenhauer that death is the end of our conscious experience, and to assume so seems like a bunch of materialist crap. The big-bang and nihilism aren’t the only, or most likely explanations for our existence folks. To assume otherwise in order to take matters into our own hands seems like a recipe for disaster.

I would also argue that Castagnet (and myself) thinks that the end of death is also something not good for society for two reasons a). the prolongation of defective systems and b). the inability to find our place in the world.

La prolongación de la vida suele estar acompañada de una prolongación del fascismo.

The prolongation of life usually is accompanied by a prolongation of fascism. (Translation mine).

There’s an idea in science that posits that new theories turn over at the same rate as tenured professors. That is that no one really changes their minds, and death is required for new theories to come to prominence. The same seems to be true for government, which in “Los cuerpos del verano” is the same shitty bureaucracy that we have to deal with in the 21st century, accompanied by the same shitty half-feudalism, half-capitalism. Nothing ever changes because no one ever dies and no one ever changes their minds.

The other issue with a lack of death is how byzantine family and personal relationships become. Ramiro is living as an adult with his grandchildren who are also adults along with great-grandchildren who don’t understand what their relation to him is. His grandson changes genders. He also ends up in a romantic relationship with his wife’s granddaughter from a second marriage. His daughter still communicates to him from the internet. There is a scene where his love interest (his step-granddaughter?) is scratching out the family tree she has on her wall because it’s become imposible to keep up with. Ramiro no longer has any grounding as to who or what he is in relation to others anymore as who exactly he is relating himself to is constantly changing. Of course this happens in our world too, with people changing jobs, spouses, genders, etc. but in “Los Cuerpos del Verano” its turned up to 11. This culminates in Ramiro actually being satisfied when he is reincarnated as a horse: at least that’s a role he can actually play and understand.

We no longer (and have never) controlled technological development. It controls us

We commonly hold this two harmful and naive ideas about technology in our society: that it’s neutral and that we control its development. Neil Postman in his book Technopoly makes a convincing argument against the first postulate, which I reviewed here. I think Castagnet makes an argument the second point in this book. First of all, he literally says it:

La tecnología no es racional; con suerte, es un caballo desbocado que echa espuma por la boca e intenta desbarrancarse cada vez que puede. Nuestro problema es que la cultura está enganchada a ese caballo.

Technology isn’t rational; with luck, it is a runaway horse foaming at the mouth and trying to jump off a cliff every time it can. Our problem is that culture is tied to this horse (translation mine).

He also shows it. One of Ramiro’s great-grandson’s kills the other so that they can be with their grandfather (who dies during the book) on the net. Reincarnation has merely extended the problem of unemployment and hiring discrimination. Who wants to hire a dead person in a crappy body? And it’s not enough to reincarnate in human bodies, we have to try in animals too, even though no one wanted that.

I cannot recommend this book highly enough to Spanish and English readers alike. I hope it makes you think as much as it did for me. If you enjoyed this review please subscribe. If you have book recommendations please leave them in the comments.

The new underclass in the book consists of “panchamas” or untouchables who choose to reincarnate in their own bodies.